I hear a lot of startup folk talk about exercising (privately held) stock options as more of a tax analysis than an investing analysis. I think that’s backwards. While it’s critical to understand tax implications of exercising options (and, indeed, it can impact your ultimate decision to exercise), thinking like an investor and evaluating your own employer is Step #1. After all, if you wouldn’t invest in your employer, taxes are a moot point.

A quick aside: for those looking for more technical write-ups on options, I’d highly recommend Holloway’s Guide to Equity Compensation. It’s comprehensive and covers all the critical terms. This is more an approach to thinking about your options and whether to pull the trigger at all.

Also, note that luck plays a heavy hand in startup outcomes, so while this might all seem eminently logical, it’s nearly impossible to account for the winds of fate and luck that could still help an otherwise lackluster company exit at profitable terms.

Oh, and don’t exclusively rely on this post. If you’re actually looking at exercising, talk to a lawyer or accountant, in addition to thinking about the business. I’m not a lawyer (didn’t quite get there) and I’m not an accountant. I just repeatedly make fun Google Sheet scenario calculators to make major life decisions, like exercising options or buying a house.

Okay, with my caveats aside….

You know simultaneously more than the typical investor

Regardless of your position and role, it’s helpful to take a step outside of your company and look at it through your own checkbook: would you invest?

First thing to note is your informational advantage. As an employee for at least a year (which is how long it typically takes to vest any options whatsoever), you casually float around in information the most successful investors in the world have to hustle to get a taste of.

Glenn Kelman, CEO of publicly-listed real estate site Redfin, remembers Fixel showing up in Seattle for the afternoon with a duffel bag stuffed with papers, Fixel’s own research and diligence on Redfin, prior to a first meeting. “He said, I interviewed your customers, your employees, your ex-employees, your competitors. And we want to talk about why margins in San Diego in Q3 of last year were off.”

Forbes article about renown venture investor, Lee Fixel

You’ve likely had your first all hands’ meeting, you’ve hopefully seen your company’s quarterly financial projections and know whether you’re hitting goals or not, you see how well your product and engineering teams execute, and you might even get weekly or monthly company-wide email updates from your marketing team.

This is all gold. Put it together and you can answer questions like:

Is my leadership team setting realistic, achievable goals? I.e., are we consistently hitting those goals and do they represent meaningful growth (or see these metrics and benchmarks for SaaS)?

Are we building quality product that makes customers happy? I.e., is our NPS, product-market-fit score, or retention good, great, or increasing?

Is our marketing team driving a lot of cost-efficient leads/users/customers?

Are my peers happy? Is morale high? Does the sales team feel excited? Are account managers, customer success, or customer support invigorated? Are people quitting at alarming rates? Why?

Based on all of the above, and your own experience, do you trust and respect your leadership team?

I personally think the last question is one of the most important, but hardest, to face. It takes effort and time to cut through many of the personas leaders at companies begin to take on before you see the human behind the title. However, this is the human — flaws and all — leading your company, interacting with investors, and directing strategy. You should feel good about them.

When asking yourself these questions, it’s important to realize that even the best companies can feel chaotic, messy, and dysfunctional when you’re inside looking out. It’s incredibly easy to get caught in a grass-is-always-greener mentality: why does that other startup look so put together?

The truth is: it’s probably just as messy at their company. Startups are hard and inherently chaotic! But, you should be able to peel away some of those gut reactions by answering the above questions with the information you have.

And less than the typical investor

Where an investor absolutely trounces you is when it comes to your company’s cap table and the terms of the deal. Companies are often cagey about telling employees who owns how much of the company. Some companies are even cagey about telling employees how many fully diluted shares there are, which makes it impossible for you to know just how much of the company you own or have the right to own. (Compare to eShares/Carta, which actually gives you the break point — in your offer letter — at which investors would be paid out and you, as a common shareholder, would see money. We can all aspire to be as transparent as Carta.)

You could be in either of two scenarios:

Your company is doing well enough that the terms are kind of irrelevant (e.g., Facebook, Google, Amazon, etc.). (Even for the best, this isn’t always the case, but if you were an employee before the above companies went public, you made money.)

Your company raised a lot of capital and/or it’s not abundantly clear how big it’ll go.

Most startup employees find themselves in the second camp. What terms do you need to know? Because this is a detective game and you may not get everything you’d like, I’m going to focus just on the Must Have information.

Must Have Information

Fully diluted number of shares. This is the number of shares there’d be if all financial instruments, like warrants, convertible notes, etc. converted to equity (i.e., shares) and also includes all shares in an option pool, even if unissued.

Take this number and divide it into your number of vested shares. That’s how much of the company you own on a fully diluted basis.

For example, if I have 10,000 vested shares and there are 1,000,000 fully diluted shares, I have the right to own 1%.

Like I mentioned above, getting this number can sometimes be difficult because companies are cagey. However, you must insist you know this number as, without it, you have no idea how much of the company you own. (You should also ask this question before you’re hired, too, when presented with an offer that includes equity.)

Total amount of capital raised. This is how much money your company has raised. You can usually find this total by searching Crunchbase. The bigger this number, the higher the exit value needs to be before you see a dime. I’ll explain.

Venture capitalists (usually) invest money into companies in exchange for preferred shares. They’re called preferred shares because they come with preferences that common shareholders, like employees and founders, don’t have. Some of those preferences are things like board membership, liquidation preferences, what to do if the company raises a future round at a lower valuation than the current round, and whether the investor is participating or non-participating when it comes time for an exit. I’ll explain more later, but for now, you care about this amount because if your company is acquired, it’s most likely that investors get this amount back before common shareholders receive any money. So, if your company raises $50 million, but sells for $25 million, it’s highly likely common shareholders won’t get anything.

Your company’s latest 409A valuation. Startups typically hire valuation consultants to provide a Section 409A valuation (federally mandated) every 12 months or so. Those consultants value the company using some semblance of voodoo and spreadsheet wizardry. The bottom line is that you care about that valuation because it’s the price that determines your tax liability when you exercise (common types of privately held) options.

If you have these three pieces of information, you can at least calculate a rough minimum exit price for you to make any money, and then consider the likelihood of your company reaching that target.

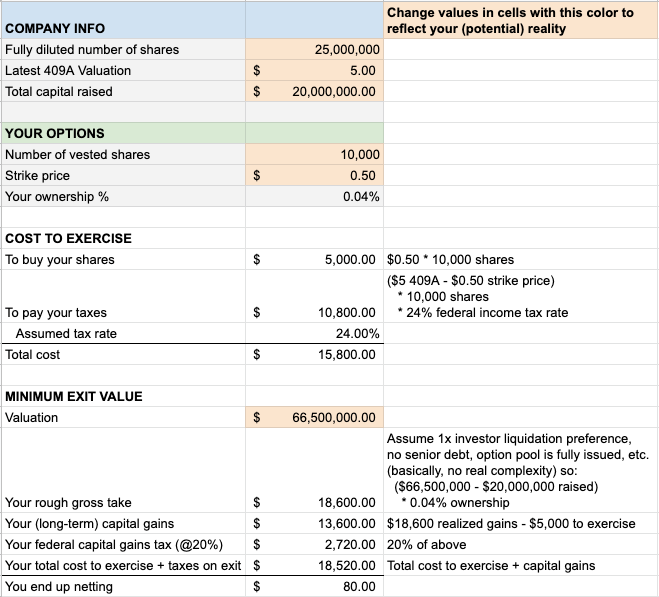

In the example below, the company would have to exit at around $66,500,000 for me, the employee with 10,000 vested shares, to make any money, after considering taxes and how much it cost me to exercise in the first place.

Your question becomes: how likely do you think it is that your company can exit for at least that value? Then, your next question quickly becomes: is that amount of money worth stomaching the anxieties, the ups-and-downs of the company on its journey, not to mention the $15,800 it’ll cost you out-of-pocket to exercise your shares? At what amount of money is it worth the ride? And what do you think is the likelihood of an exit at that value?

Hopefully this all gives you a sense of how to value your options and whether to exercise or not. I found this path personally helpful and would love to hear how you would improve it.

Final note: there’s loads of information that, if you can get it, will refine your calculation and thus your analysis. For example, it’s nice to know whether your company has any debt that would have to be paid before shareholders, or whether any of your VCs are participating (i.e., they get their liquidation preference AND their share of the gains) or non-participating (i.e., they get either their liquidation preference OR their share of the gains, whichever is more). I side step that because this post could get a lot longer, but let me know and I’d be happy to follow up with that stuff in a sequel post.